Author: Neelam, Student at Army Institute of Law, Mohali

ABSTRACT

The COVID 19 pandemic brought the entire world to an economic standstill. With an aim to revive the economy, a number of Indian states came up with major reforms which led to the dilution of principle labour laws. The reforms introduced by the states are in complete violation of the Constitutional provisions. On top of that, sudden suspension of labour laws puts the entire labour class under the threat and risks of bondage labour, lower wages to women, lack of job security and increased risk to the health and security of all workers. With the dilution of these laws, there will be no rules governing the hiring and firing of employees and the workers will be left at the mercy of the employers. The reforms that have been brought in do not comply with India’s international obligation as under the International Labour Organization Convention, which India ratified hundred years ago. There is very limited evidence to support the idea that introducing flexibility or suspending labor laws would boost jobs or attract more investment. Among the constraints that could affect investment flows, labour law rigidity does not feature among the top five. Overall, a stronger, although a little more complex, solution will be to finish the process of developing a comprehensive integrated legal system for labour that is light on compliance and administrative standards while ensuring that worker’s rights are protected. This will help to attract the right kind of investment while also avoiding potential worker abuse. Workers are and will continue to be increasingly important contributors in the workplace, necessitating the attention and cooperation of governments and other related stakeholders. There is an urgent need to press for greater awareness of the advantages and benefits that migrant workers bring to the states and the country, as well as for policymakers to take a more pro-migrant stance.

Keywords: labour, suspension, rights, government, migrants, pandemic.

INTRODUCTION

The Covid 19 pandemic has engulfed the entire world in public health and economic crisis. Under the lockdown the entire nation was brought to an economic halt and millions of people, especially migrant and informal sector workers and laborers were immediately left jobless. The number of people who lost their means of livelihood cannot be comprehended as it is difficult to capture the employment status of migrating workers. With an aim to minimize the impact of the pandemic and incentivize the economic activities, some of the State governments came up with huge, sweeping changes in their labour laws by way of amendments. However, this move did not work in the interest of labourers, who are one of the most vulnerable sections that have been impacted by the pandemic. Labour law is a subject which has been debated over for decades. One view that persists in the society is that our labour laws are a stumbling block in encouragement of investment and expansion of industries. They say that because of the rights which are enshrined in the labour laws, there have been instances of deindustrialization in certain regions and areas. The subject of labour laws falls under the Concurrent List of the Indian constitution and therefore, both parliament and State legislature contain the power to make laws regulating labour. There are, currently, over 200 state laws and 50 central laws existing which govern different facets of labour including the settlement of industrial disputes, working conditions, wages and social security. The COVID-19 crisis now appears to be being used as an excuse to drive through the unfinished ‘reforms agenda’ of increasing working hours, lowering wages to the bare minimum, cutting social security benefits, allowing the use of contract labour for any type of job, loosening dismissal rules, curtailing trade union rights, and reducing labour inspection. The central government has been attempting to expand factory workers’ working hours for nearly six years.[1]

OBJECTIVES OF STUDY

The objectives of the study are:

To know whether suspension of labour laws is actually going to encourage the industries to invest in the state’s concern or these measures will result in the exploitation of labour without a matching improvement in investment.

In this research paper, I have made an attempt to throw some light on labour rights and conditions of migrant labour in India vis-à-vis the pandemic. The research is descriptive in nature and is built on primary and secondary data reported in various government and non-government studies.

SUSPENSION OF LABOUR LAWS

A law named “Uttar Pradesh Temporary Exemption from Labour laws,” was promulgated by way of an ordinance by the Uttar Pradesh State Government on 8th May 2020. This law allows the state to grant sweeping exemptions from labour laws.[2] The state government justified this action by stating that liberalization or complete exemption of most of the labour laws will help investments to flow in to Uttar Pradesh and thereby there would be economic revival and at the same time, creation of jobs. These are the assumptions that underlie the move by Uttar Pradesh, but, in my opinion these are extremely misplaced assumptions. As a result of this, 35 out of 38 existing labour laws will remain suspended in the state for the next three years and these laws will not apply to employers or industries or enterprises in Uttar Pradesh for the said time.[3]

The only labour laws that remain functional in the state are The Workmen Compensation Act, 1923, the Bonded Labour System (Abolition) Act, 1976 and the Building and Other Construction Workers Act, 1996, along with Section 5 of the payment of wages Act 1936 which says that the workers shall be apid their wages within the prescribed limit of time frame.[4] Beyond this, any laws related to deployment of women and children will not be diluted under the ordinance. The states of Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Gujarat, Himachal Pradesh, Orissa, Punjab etc walked on the same path and introduced similar provisions regarding the labour laws, although in smaller scope.

LABOUR RIGHTS AT RISK

Although the changes introduced are well intended and focus at promoting investment and industries, the unintended ramifications of such actions can be quite serious in nature. The sudden suspension of labour laws puts the entire labour class under the threat and risks of bondage labour, lower wages to women, lack of job security and increased risk to the health and security of all workers. With the dilution of the Minimum Wages Act, 1948, wages received by the workers would not be regulated. Gunjan Singh, who specializes in labour laws, said, “The consequence of suspending The Minimum Wages Act is forcing labourers into bonded labour. Indian jurisprudence recognises that payment below minimum wages amounts to a situation of bondage.”[5] In the Bandhua Mukti Morcha[6] judgement of 1984, the Supreme Court affirmed that payment below the minimum wage would amount to situation of bondage. The court also provided that the State government is also responsible for identifying, realizing and rehabilitating bonded labourers. It was further decided that every worker who is forced to work as bonded labour is stripped off his liberty. Such a person is equal to a slave and his freedom concerning employment is taken away from him and he is subjected to forced labour. In the case of Sanjit Roy v. The State of Rajasthan[7] it was also held by the Supreme Court that if the worker is not paid the minimum wage, the work then constitutes as “forced labour” in complete violation of the Indian Constitution.

The Factories Act, 1948, provides for a legal framework for workers’ fundamental rights, such as fair working hours, leave time and overpay. Suspension of this act poses a great risk to the employee safety of the worker. A situation like this would be a breach of Article 21 of the Indian Constitution, which guarantees not only mere existence but also the right to dignity and the all other aspects of a person’s life that make it meaningful. Thus, forcing workers to work beyond their mandated work hours would inevitably impede their holistic development and lead to exploitation, which would be in violation of their right to a dignified life as guaranteed under Article 21 and Article 23 of the Indian Constitution, which protects workers from exploitation and forced labour. The suspension of this law would most certainly jeopardize important policies, repair and inspection of other safety and critical equipments. Employers are no longer required to provide minimum standards of protection and care to the employees.

The labour departments of Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and Himachal Pradesh released simultaneous notices extending factory workers’ working hours to a maximum of 12 hours per day and 72 hours per week, citing a public emergency. Section 5 of the Factories Act was used to issue the notices, which were valid for three months. Around the same time, the Punjab Labor Department issued a similar order under section 65 of the Factories Act, allowing factories to be exempted from the Act’s daily and weekly work hours requirements in order to deal with extreme workloads.[8] However, it is important to note that this authority can only be used in the event of a “national emergency.” For the purposes of the Factories Act, a public emergency is described as a “grave emergency in which the security of India or any part of its territory is threatened, whether by invasion, external aggression, or internal disturbance.” COVID-19 may be the most destructive pandemic in human history, but it still does not count as a national emergency under the new version of the Factories Act, 1948.[9] The fact that long working hour may jeopardize worker’s health and safety appears to have gone completely unnoticed.

Similarly, the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 says that permanent employees may only be fired for a legitimate purpose with the approval of the appropriate government office. This act protects employees from being fired for reasons that aren’t fair such as their membership in a union or involvement in a protest for better remuneration or working conditions. With the dilution of this law, there will be no rules governing the hiring and firing of employees. Ironically, despite the Supreme Court of India acknowledging the right to access to justice as a constitutional right in the case of Anita Kushwaha v. Pushap Sadan[10], the grievance redressal procedure for them, as given in the Industrial Disputes Act, is also unavailable due to the suspension of the laws.

For a period of 1000 days from the date of publication of the notification, the government of Madhya Pradesh issued a notification exempting new factories from the provisions of the Industrial Disputes Act, except those relating to layoffs, retrenchment, and closure. For a span of 1000 days, workers in newly founded factories would be unable to exercise their freedom of association and collective bargaining rights[11].

The Uttar Pradesh ordinance also seeks to suspend the Trade Unions Act, 1926, which empowers workers to form trade unions for the regulation of work-related matters between employers and employees. The suspension of the act is in violation of the Article 19(1)(c) of the Indian Constitution which guarantees the right to form associations and unions and includes the right to form trade unions, as held in the case of Raja Kulkarni v. State of Bombay.[12] Furthermore, those labour unions speak for and represent other workers in front of the authority in the event of a dispute, which is critical in any collective bargaining structure. The very justification for the presence of a labour union is to counterbalance the employer’s bargaining power.

VIOLATIONS OF THE INTERNATIONAL LABOUR ORGANISATION (ILO)

India is signatory to the International Labour Organisation Convention (ILO). The aim of this Convention is to improve economic and working conditions so that all employees, employers and governments have a stake in long term stability, prosperity and development[13]. India has also ratified the Tripartite Consultations (International Labour Standards) Convention, 1976, which codifies ILO’s spirit of tripartite consultation between the country, the employer and the workers. But these ordinances have been introduced unilaterally and inspections have been done away. These ordinances seem to be in direct breach of the International Labour Organisation Conventions, which are internationally recognized benchmark for what domestic labour laws should aspire to be.[14]

The International Labour Organisation wrote to Prime Minister Narendra Modi, urging him to ensure that the states uphold India’s international labour commitments. Several trade union filed complaints about impending labour abuses, including violations of the fundamental rights of millions of migrants across the world, promoting this communication.[15] In its declaration, the ILO emphasised that any changes to India’s labour laws should be made in compliance with the organization’s Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work. Though applauding India’s long-term commitment to the ILO norm, the statement indicated that now is the time to “strengthen social dialogue, collective bargaining, and labour relations mechanisms and structures for implementing solutions” [16]

These ordinances, according to me, unleash labour market anarchy and we should be afraid that this virus of labour flexibility will be far more dangerous than the COVID virus because it will impact not only workers in the unorganized sector, who are not covered by these labour laws, but also the organized sector. ILO talks about formalizing informality, but instead UP, Madhya Pradesh and few other states are in-formalizing formality. It is not acceptable that the labour rights which have been constructed by an effort of over 150 years will be blown away by ordinances. This kind of a paradigm will push us and the entire labour population back to the 19th century and this would be a very unfortunate historical reversal.

WILL SUSPENSION OF LABOUR LAWS BOOST INVESTMENT?

There is very limited evidence that introducing flexibility or suspending labor laws would boost jobs or attract more investment. It is very pertinent to here, that, it is not the labour laws rigidity that constraints investment inflows. There are other economic aspects related to the ease of doing business like extensive infrastructure, high availability of muscle power, political and economic stability, hassle free and investor free environment, etc, which increase investment. States like Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Delhi NCR, and Maharashtra have largely succeeded in attracting Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) primarily because these states are rich in infrastructure facilities, skilled muscle power, and investor friendly environment, among other elements of ease of doing business. Uttar Pradesh, on the other hand does not possess many of these facilities and advantages. According to the Annual Survey of Industries 2016-17[17], there are only about 12,000 factories in the state employing less than eight lakh workers. Is this an economic justification?

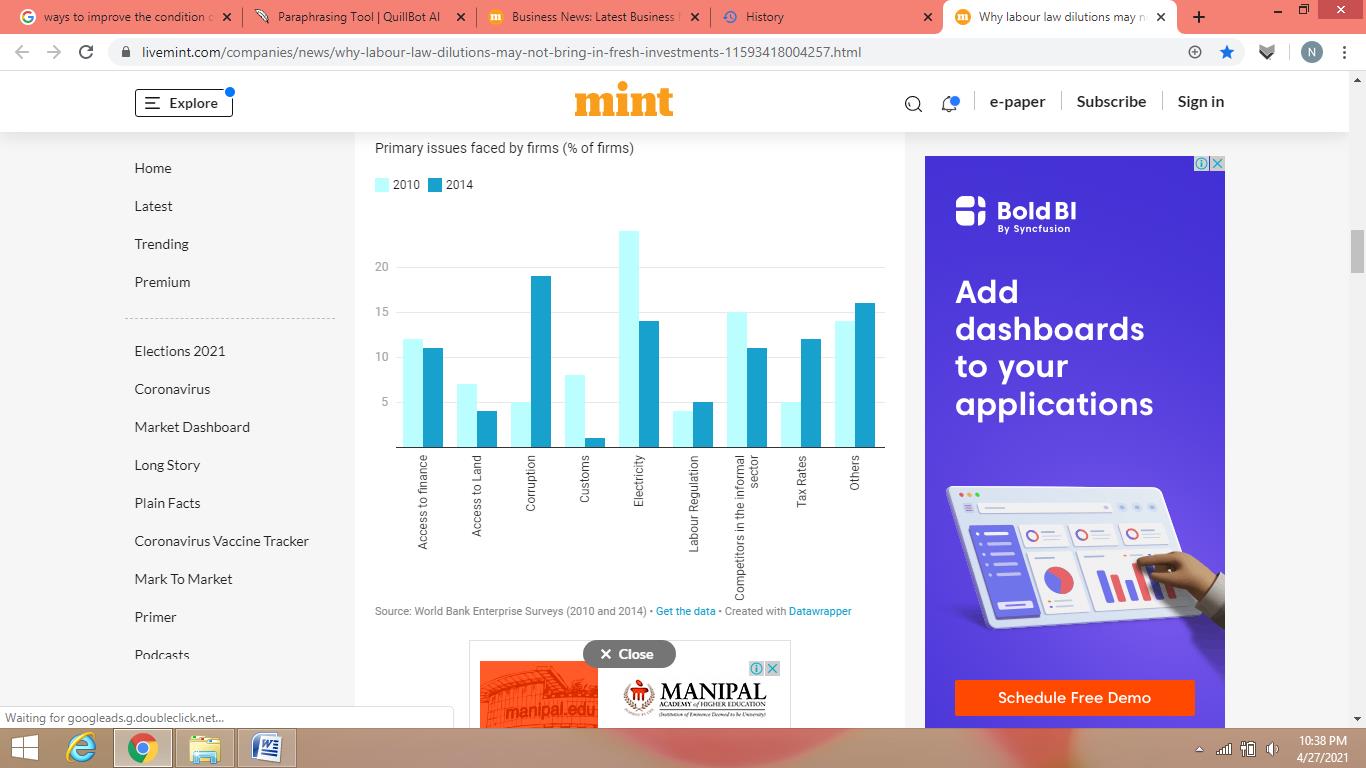

We need to realize that among the constraints that could affect investment flows, labour law rigidity will not be accounted among the top five. In the World Bank Enterprise Surveys (ES), 2014, which polled 9,281 businesses across India, it was found that less than 5% of businesses cited labour regulation as a major stumbling block to their operations. After the 2010 ES round, this number has scarcely changed[18]. Skilled muscle power, extensive infrastructure and various other aspects mentioned above are responsible for investment or lack of investment in the state. The Uttar Pradesh government must rather look at revamping skill development program and also restructure the educational institutions, particularly ITI’s and such, to make available a large amount of surplus power.

For Indian businesses, electricity, corruption, and tax rates are more significant constraints than labour regulations.

Figure 1 – Primary issues faced by firms[19]

We need to ponder over the fact that why do people from Uttar Pradesh feel the need to migrate. The very fact that millions of workers migrate from the state of Uttar Pradesh points that there is something wrong in the way the economic policies and the labour laws are being envisaged and administered. Investments will flow only when the employers are assured that they could have a dialogue with recognized trade unions and labour standards are good and as a result the productivity and economic efficiency will increase and thereby, both the employers and the country could reap the benefits of it. But, in the name of labour law reforms and granting labour flexibility to employers the state governments are making an attempt to weaken the labour standards.

Finally, contrary to the popular narrative, while India rates 58th out of 140 countries in the World Economic Forums’s Global Competitiveness Index, it ranks 33rd on the flexibility of labour markets. China, on the other hand, is ranked 62nd in terms of labour markets, despite being ranked 28th overall. Clearly, a lack of competitive labour markets is not the primary cause of India’s low competitiveness, and there is little indication that just changing labour regulations will attract foreign investment, particularly from companies eager to leave China.[20]

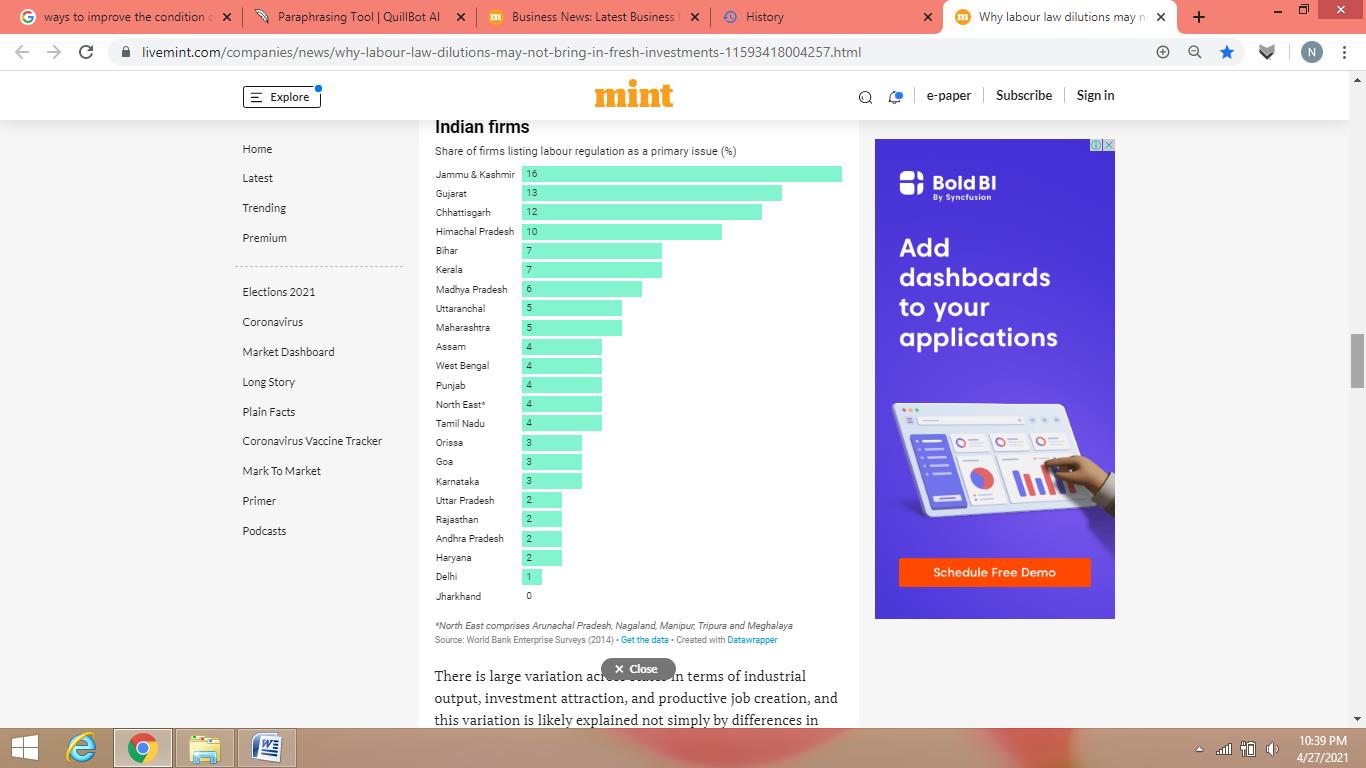

For Indian businesses, labour laws are seldom a major stumbling block.

Figure 2 – Share of firms listing labour regulation as a primary cause[21]

In terms of attracting foreign investors to India, inflexible labour laws rank fifth among the five least appealing variables, trailing only transportation and logistic infrastructure, the legislative and administrative climate, corporate taxation system, and overall ease of doing business. The most appealing aspects of India, according to the World Bank survey, are competitive labour rates, strong labour skills, and a wide domestic market[22].

Overall, a stronger, although a little more complex, solution will be to finish the process of developing a comprehensive integrated legal system for labour that is light on compliance and administrative standards while ensuring that worker’s rights are protected. This will help to attract the right kind of investment while also avoiding potential worker abuse.

STEPS TO BE TAKEN – FOR BETTER CONDITIONS OF WORK

Overall, the pandemic, as well as the subsequent shutdowns and social consequences, were not the primary cause of migrant workers’ suffering in India. Instead, it was a system that mostly left migrant workers at the mercy of a system that had little or no social security. The migration of millions of workers from India’s poorer areas, mainly in the north and east, to the more prosperous cities in the south and west, has fueled the country’s economic growth in recent decades. Many of them migrate due to lack of employment and resources at home, but once they cross state lines, they are instantly vulnerable. Without a doubt, workers are and will continue to be increasingly important in the workplace, necessitating the attention and cooperation of governments and other related stakeholders.

There is a need to press for greater awareness of the advantages that migrant workers bring to the states and the country, as well as for policymakers to take a more pro-migrant stance.

This pandemic is an excellent opportunity for the government to create new types of economic structures and institutions in the country, especially in the rural areas. The lack of fair treatment of employees has been a glaring flaw in this dispersed production model so far.

Steps must be taken to increase migrant workers’ engagement in unions and organizations to ensure that their voices are heard in social dialogue processes. Workers may be protected from abuse if they join a union.

With rapid technological advancements transforming the landscape of jobs across all sectors, India’s migrant workers must be equipped not only to remain relevant, but also to benefit from these changes. So far, 69 lakh people have been trained under the Pradhan Mantri Kaushal Vikas Yojana, a skill development programme aimed at youth; no such programme exists for migrant labourers. A similar skill mapping and skill growth roadmap for migrant workers must be developed by the Ministry of Skill Development and Entrepreneurship. Both in their home state and in the destination state, the capacity development programme must be matched to business requirements.[23]

CONCLUSION

The economy of the country has suffered huge backlashes due to the pandemic induced lockdown and the government is enthusiastic about its goal of increasing investment and jobs by relaxing labour laws. I believe, in the name of COVID 19 and labour shortages, the state governments are introducing uncalled for, sweeping changes in labour laws which takes us back to the nineteenth century labour market model where an individual worker had to negotiate with an individual employer, and thereby, getting exploited. While it could seem that such steps would only be in effect for a short time, they may be a sign of things to come, and once the waters have been checked, they may become a permanent feature. Although the government can justify such retrograde measures by arguing that they are appropriate to jumpstart the economy, attract investment, and create jobs, the fact remains that such measures violate workers’ constitutional rights and human rights and cannot be justified on any basis. Labour rights are human rights, and the Indian government cannot ignore its constitutional obligations or the commitments it has made by ratifying various ILO Conventions, which obligate it to promote decent work in conditions of equality, justice, protection, and dignity. So, in these unprecedented times, the low labour class must be strengthened and should not be diluted. Even a global pandemic caused by COVID-19 does not excuse the deliberate underutilization of the labour force. It is especially important for the government to protect workers’ interests in these times.

REFERENCES

[1]Ramapriya Gopalakrishnan, (2020, May 20), Changes in labour law will turn the clock back by over a century. Medium – https://thewire.in/labour/labour-laws-changes-turning-clock-back

[2] Namita Bajpai,( 2020, March 08), UP suspends major labour laws for three years to attract investors. Medium – https://www.newindianexpress.com/nation/2020/may/08/up-suspends-major-labour-laws-for-3-years-to-attract-investors-2140784.html

[3] Prashant Srivastava, (2020, March 08), Key labour laws scrapped in UP for 3 yrs as Yogi govt brings major reform to restart economy. Medium – https://theprint.in/economy/key-labour-laws-scrapped-in-up-for-3-yrs-as-yogi-govt-brings-major-reform-to-restart-economy/416925/

[4] Winy Daigavane and Pavan Belmannu, (2020, March 20), Impact of the Global Pandemic on Indian Labour Laws. Medium – https://www.jurist.org/commentary/2020/05/daigavane-belmannu-labor-law-suspensions-india/

[5] Betwa Sharma, (2020, May 08), UP Govt’s Suspension Of Labour Laws Could Greenlight Bonded Labour. Here’s Why. Medium – https://www.huffpost.com/archive/in/entry/up-govt-s-suspension-of-labour-laws_in_5eb558a5c5b6a6733541543e

[6] Bandhua Mukti Morcha v. Union of India & others (AIR 1984 SC 802)

[7] Sanjit Roy vs. the State of Rajasthan (AIR 1983 SC 328)

[8] Vinay Umarji (2020, May 09), After UP, Gujarat offers 1200-day Labour Law exemptions for New Industrial Investments. Medium – https://thewire.in/economy/gujarat-labour-law-exemption-new-industries-covid-19

[9] Justice V Gopala Gowda, (2020, June 20), Dilution of Labour Laws is Unconstitutional Medium – https://www.newindianexpress.com/opinions/2020/jun/20/dilution-of-labour-laws-is-unconstitutional-2158931.html

[10] Anita Kushwaha v. Pushap Sudan (2016) 8 SCC 409

[11] Supra note 1

[12] Raja Kulkarni v. State of Bombay. Medium – https://indiankanoon.org/doc/620843/

[13] Covid 19: India should amend labour laws only after consulting workers and employers, says ILO. (2020, May 14). Scroll.in Medium – https://scroll.in/latest/961977/covid-19-india-should-amend-labour-laws-only-after-consulting-workers-and-employers-says-ilo

[14] Supra note 7

[15] Somesh Jha, (2020, May 26), ILO reaches out to PM Modi over labour law changes in various states. Medium – https://www.business-standard.com/article/economic-revival/ilo-reaches-out-to-pm-modi-over-labour-law-changes-in-various-states-120052500335_1.html

[16] Supra note 9

[17] India – Annual Survey of Industries 2016-17. Retrieved on 2020, April 22. Medium – http://microdata.gov.in/nada43/index.php/catalog/145

[18] Kartik Alikeswaran, Samya Mehraaj, Ayushman Singh, (2020, June 29), Why labour law dilutions may not bring in fresh investments. Medium – https://www.livemint.com/companies/news/why-labour-law-dilutions-may-not-bring-in-fresh-investments-11593418004257.html

[19] [Primary issues faced by firms] World bank Enterprise Surveys (2010 and 2014), https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/en/data/exploreeconomies/2014/india

[20] Rishikesha T Krishnan, Kunal Kanungo, Kapil Kanungo, (2020, May 13), Are labour Law reforms the panacea to the investment problems?, Medium – https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/are-labour-law-reforms-the-panacea-to-the-investment-problem/article31572080.ece

[21] [Share of firms listing labour regulation as a primary cause] World Bank Enterprise Survey (2010 and 2014) https://www.enterprisesurveys.org/en/data/exploreeconomies/2014/india

[22] Supra note 13

[23] Prasanna Karthik, (2020, July 01), The migrant labour crisis must push for structural reforms, Medium – https://www.orfonline.org/expert-speak/migrant-labour-crisis-must-push-structural-reforms-68874/